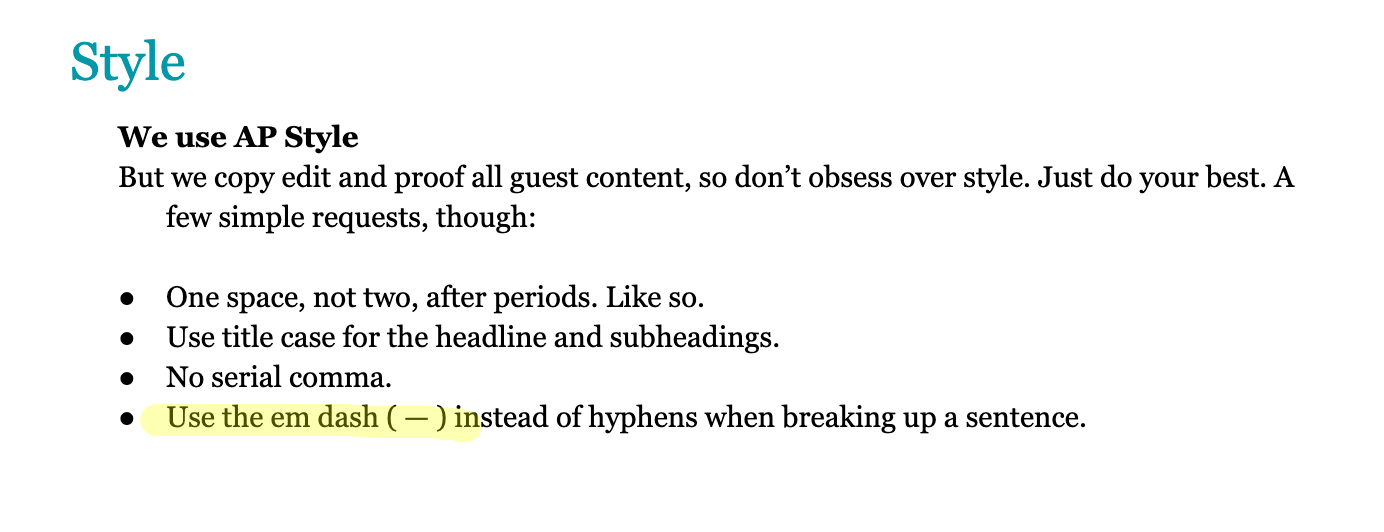

When I started working at Brafton in 2015, I was trained on Brafton editorial standards. We follow AP Style (most of the time); we spell “white paper” as two words; we don’t use the Oxford comma; we do use the em dash.

Honest — I have proof — here’s a screenshot from our style guide:

“Where is the em dash key?” I asked on my first day.

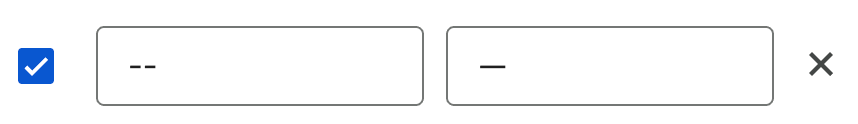

“There isn’t one,” said Jess, the woman training me, advising me to set up a custom rule in Google Docs to automatically convert every double-hyphen into an em dash. Easy-peasy.

I ignored her advice, instead saving this link to The Punctuation Guide website to my bookmarks bar and copy-pasting the em dash whenever and wherever I used it for the next five years. Then I made the shortcut.

Was copy-pasting this dash a tedious endeavor when writing more than 2,000 words daily? I mean, yes 😅 But that’s what I did, so dedicated was I to the usage of this form of punctuation (and to not setting up shortcuts).

Not that I overused it (much). It doesn’t belong everywhere, or even in every article. But it’s become such a familiar component of my writing that I, like many other professional writers, was at first amused at the growing backlash against the punctuation, then just frustrated.

Subscribe to the ai marketer

Weekly updates on all things ai in marketing.

A Brief History — and Explanation — of Em Dash Bashing

Initially, I was confused; why would using this basic, very common punctuation mark signal AI involvement? It’s as though saying the comma is a sign of AI writing, or that the color blue is a sign of AI imagery.

People aren’t taking this seriously, right? This is like when bots convinced Cracker Barrel that everyone hated their rebrand?

But soon enough, the sentiment started showing up at work. Non-writers’ feedback came with sidenotes about removing em dashes so my or my team’s (real, human) writing wouldn’t “look too AI.”

They were apologetic, emphasizing that they know it’s not AI-generated but … just in case.

That’s when I realized: Not everyone has the same relationship with the em dash as me. Why?

Because not everyone is a writer. 🤯 (Sometimes, as a writer, I assume everyone else is, too.)

When I came across Nitsuh Abebe’s take on it in The New York Times Magazine, it all came together for me.

“The dash is a time-honored and exceedingly normal tool for constructing sentences!” Abebe emphasized, just before illuminating the heart of the issue:

ChatGPT (like other AI tools) is trained on printed works. On published pieces. Written by professional writers (who use the em dash confidently).

But ChatGPT, largely, isn’t generating content for writers. More often than not, it’s the non-writer asking ChatGPT to generate copy for them. And that’s when they see it: a punctuation that few keyboards support out of the box; one reserved for novels and essays; a mark they’ve never even considered dropping into a text or email.

Abebe concludes that this negative reaction is a product of how we communicate today. Until very recently, person-to-person communication was done mainly with our voice. We talked to each other. Today, it’s just as likely that we’re “talking” to each other via written communication: texts, chats, DMs, etc.

But there is a history of em-dash-hate that predates the onset of ubiquitous AI. I encountered it one day in approximately 2017 on a train ride home from work. In a 2011 opinion piece for Slate, Noreen Malone argued that the em dash was overused by writers, resulting in clunky prose filled with interruptions.

“The problem with the dash—as you may have noticed!—is that it discourages truly efficient writing,” Malone wrote, highlighting the problem at hand. “It also—and this might be its worst sin—disrupts the flow of a sentence.”

She wasn’t alone in her view, listing several professionals who had, and had published, similar opinions. She points to the notion Philip B. Corbett (who she notes was the New York Times’ associate managing editor for standards) had that “Sometimes a procession of such punctuation is a hint that a sentence is overstuffed or needs rethinking.”

I read the article because the title was funny: “The Case—Please Hear Me Out—Against the Em Dash” and because I was expecting to be incensed by her case against the dash I’d been painstakingly pasting over double-hyphens. But she and Corbett were right: It can produce unnecessarily winding sentences if not used carefully.

And that, actually, is what brings me back to AI-generated copy.

On “Natural Sounding” AI Copy

Does your ChatGPT output need rethinking? Yes. Yes, it does. You do have to review it before you use it. And if it doesn’t “sound” like you (or your brand), then it needs refinement.

But should the presence of particular punctuation sound your alarms? Maybe; brand guidelines commonly dictate how copy should look and read, and that includes specifying terms, constructions and, yes, even punctuation.

So, where do we go from here — this odd moment in time where the em dash is demonized as a sign of AI writing (and where AI writing is, itself, also demonized)? Here’s my take, as a writer and also as a marketer:

For Marketers Producing Content

First and foremost, if you’re generating AI content, it’s critical to your brand integrity that you are a stringent guard against brand dilution. It’s up to you to ensure that the output reflects your brand as you intend for it to be presented.

Most of the time, generic AI tools like ChatGPT will not sound like your brand. They’ll sound like ChatGPT. The key is to either:

- Use an AI program that was built for marketers, with brand safeguards built in. (That’s why we made contentmarketing.ai.)

- Create detailed prompt structures and workflows to ensure your AI output is as close to “your brand” as possible, with a very good human review process in place, too.

Maybe that means replacing every em dash with another punctuation mark. More likely, it means going through it with a fine-toothed comb to find things like:

- Phraseology that your brand wouldn’t use.

- Formulaic structures that scream “ChatGPT wrote this!”

- Hallucinations or inaccurate information that you simply can’t publish.

- Ultra-generic information that your audience really has no need for.

- Opportunities to insert your brand’s expertise and authority.

For Organizations Working With Content Agencies

If you’re working with a content agency, you deserve to know exactly how your content was produced. If you suspect AI usage, I strongly recommend you don’t jump to conclusions.

There are tons of problems with “AI detectors,” and oftentimes, a client saying they think the content that their writer delivered “sounds like AI” is a signal that something else is amiss. The answer is to bring up the topic in a non-judgmental but inquisitive way, and have a good conversation about expectations.

If you’re curious about Brafton’s stance on the matter, it’s this: We don’t use AI in client content unless we’ve already had a conversation about it, and the client is fully on board.

For People Creating Content Outside Work

I’m not here to tell you how to use AI outside work (or even at work), but I am aware that some people do use ChatGPT or other AI tools to communicate with people in their own lives.

For example, YouTuber Evan Edinger claims to be able to identify AI writing anywhere, calling out our friend the em dash as the first telltale sign. But what interests me is his analysis of the AI-generated comment posted on his YouTube video. He actually replied to the commenter addressing his suspicion, and (a good sport indeed) the commenter admitted to it, even providing Edinger with his original prompt.

Here’s the thing: There was nothing wrong with the original comment. It was clear, kind and human. What AI did was straighten out his sentences so they read more “grammatically correct” — but also removed his personality from the comment.

So here’s my advice: Use ChatGPT if you want, but remember that your natural way of communicating is just fine in many situations. You are human, communicating with other humans, after all.

For People Engaging With Content Outside Work

And now for what I imagine is the biggest group concerned with the “ChatGPT hyphen” (let’s not let this name catch on): regular people, consuming content in their normal lives.

If you suspect something you’re reading is generated by AI, ask yourself this: How does that impact your relationship with the content? If it completely changes the way you view it, you can simply stop reading it.

A word of caution: Asking the creator if they used AI (or worse: accusing them of it) is not a neutral question at this point in time. They’ll likely take offense.

For what it’s worth, I did a quick review of 32 articles I’ve written for the Brafton Blog over the past seven years or so; 14 of them contained em dashes. The longest article (perhaps that I’ve ever written) contained 32 of them (which, arguably, is too many).

Maybe someday, the em dash backlash will die down. Or maybe it’ll become a relic of past editorial times. For now, I’ll continue to use it — because I don’t really want to change the way I write just because of AI — but I am more conscious of how so (if only to improve my sentence structure).